Introduction

My name is Geoffrey Marchal. I’m a 3D scanning enthusiast and I’ve published hundreds of 3D scans on Sketchfab. For several years I have wandered, strolling in the museums of Copenhagen and Brussels to capture as much as I can of cultural heritage. I have also been working in computer graphics (CG) for over 25 years and using Blender since 2009. I have worked on several projects that have required the digitization of small to medium scale models, mainly sculptures and other archaeological items in museums. And today, I would like to share this experience. In this tutorial, we are focusing on the most important aspect of photogrammetry:

How to take good photographs

The workflow is really easy and with this tutorial we are going to walkthrough:

- What is photogrammetry?

- Why is photogrammetry worthwhile?

- Why are photographs so important?

- What do you need for your first photoshoot?

- What are the good camera parameters?

- How do you take good photographs?

If you already have some knowledge about photogrammetry, you may go directly to section 3.

N.B. This is a hobbyist tutorial. The following tips are intended for producing casual, non-scientifically rigorous models.

1. What is photogrammetry?

Photogrammetry has been defined by American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ASPRS) as “the art, science, and technology of obtaining reliable information about physical objects and the environment, through processes of recording, measuring, and interpreting images and patterns of electromagnetic radiant energy and other phenomena.” That was a mouthful!

In common words, photogrammetry is the use of photographs to recreate a numerical 3D model on your computer.

Yes! It is as easy as it sounds! You take several photographs, usually about 100 to 300, load them into the software, click and wait for the software to do everything for you.

In short, the software will first match and stitch all the photographs together (like an inward panorama), create a point cloud, and this point cloud will be used to recreate the polygons and texture of your model.

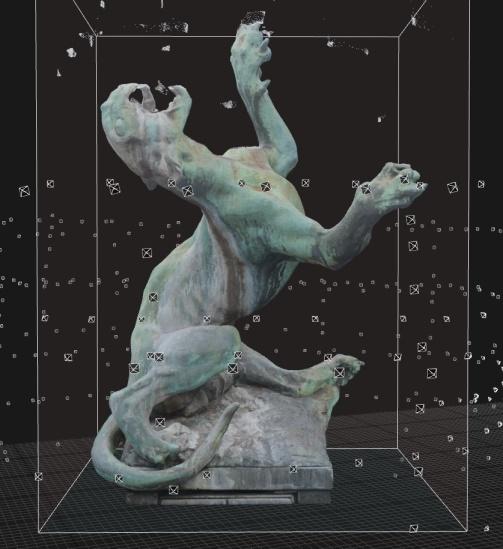

- Photo made with X-M1 FujiFilm

- Point cloud

- Textured mesh made with RealityCapture

2. Why is photogrammetry worthwhile?

Photogrammetry was my dream coming true. Since the 1990s I had been looking for a tutorial about 3D scanning but all of them involved several-thousand-dollar 3D scanners! But in 2014, free photogrammetric software such as Memento Beta and 123D Catch were released. Today, you have many options (i.e. ReCap, RealityCapture, Agisoft Metashape, 3DF Zephyr, AliceVision, Meshroom) with prices ranging from $150 to $2000. Most of these softwares even offer student/indie options at even more affordable prices! The only thing you need is a camera and a computer. And the one you have on your phone is enough to start making great 3D scans, so you do not have an excuse not to try it out.

3. Why are photographs so important?

As photogrammetry is the use of photographs to make reliable measurements, the quality of the 3D model will mainly depend on the quality of the photographs. The software is using the information contained in your photographs to reconstruct the 3D model. So, if your photographs are bad, the 3D model will be bad, too…. It’s that simple!

Keep in mind that making photographs for photogrammetry is not about making art! You aim is to take accurate, precise, shadowless, and sharp photographs. Think more about documenting your subject than creating art out of it. Your photographs should contain as much useful information as possible for the software.

4. What do you need for your first photoshoot?

Nothing except a camera! And as I said earlier, the one on your cell phone is enough for a start. Of course, as the quality of the 3D model depends on the quality of the photographs, a good camera will dramatically improve the final results.

However, before grabbing a huge Canon EOS 7D Mark II SLR or equivalent, think twice about the price and even more importantly, about the weight! Keep in mind that much of the time you may not have a tripod. And you might not want to carry around a tripod. And taking hundreds of photographs with a heavy camera will kill your wrists and arms in no time! So, aim for a good, but light camera. I personally use a FujiFilm X-M1 (no product placement). It is about 0.5 kg (1lbs), 16 MP, good in low light, easy to use, has a good auto/manual mode, and you can take more than 2000 photographs with one charged battery!

5. What are good camera parameters?

And now the main course! In 3D scanning in general, it is very important to understand the volume and shape of your model. Take a couple of minutes to look at the object at different angles. Look at the variation of the background light. Check where the light (i.e. sun, spotlight) comes from. The way you organise and structure your photoshoot will make all the difference between a failure or a success.

Cell phone camera

Most of the advice below does not apply to most cell phone cameras. Usually, cell phone cameras do not allow you to modify a lot of parameters such as ISO, exposure, F-stop. However, if you have a fancy cell phone, you might be able to change some settings. Your cell phone camera may have HDR mode available. This is a great advantage, as the photographs obtained in HDRI mode have high dynamic range, meaning that in the same photograph the shadows and overexposed areas contain a lot of details that can be used by your photogrammetry software.

Exposure

First things first, don’t forget to maintain the same exposure (the amount of light per unit area measured in exposure value -EV) for all of your photographs. Usually, you can lock the exposure on your camera. No matter where you are, sharp light will be your worst enemy (I definitely hate the sun when I’m working on photogrammetry). It casts hard shadows on your object and confuses the auto exposure/focus. In addition, if the shadows move during the shoot, this might compromise your 3D reconstruction as the varied shadows will interfere with image matching. If background light strongly varies from one shot to another, use the F-stop to standardize the exposure between photographs. If your camera has an HDR mode or something similar, it is a good idea to activate it. As explained in the cell phone section, this mode allows you to pick up details in dark and overexposed areas.

- Overexposed: no detail in the sky and some details in the object are lost.

- Correctly exposed: good amount of details in the sky and bright areas, and also in the shadows

Lens Flare

A direct light can also induce lens flare, a phenomenon wherein light is scattered or flared in a lens. This adds a dramatic effect on your photographs, sure, but remember, we are not making art. Lens flare is terrible in photogrammetry as it introduces artefacts into your final 3D model. Try to avoid direct light (from sun or indoor lighting) in your photographs! I usually play at “hide and seek” with the light, using the object as shield. It works pretty well. As a rule of thumb, no photographs are better than photographs with lens flare.

- Lens flare and light spill: If you are shooting near a bright light source (spot or window), this might create artefacts in your photographs such as lens flare (picture on the left) or light spill (picture on the right). Both will induce artefacts, noise or other problem into the generated 3D model.

ISO

Sometimes the light is pretty low (e.g., cloudy day, indoor shooting). Don’t be afraid to push up the ISO (light sensitivity of the sensor or film) to 3200, decrease the exposure time, and play with the F-stop (the ratio of the system’s focal length to the diameter of the entrance pupil). I have been known to take photographs at ISO 4000, exposure time about 1/40 sec, and F-stop 3.5. As we are talking about ISO, keep in mind you can play with it during the photo shoot. I sometimes decrease or increase the ISO to keep a decent exposure time and/or an exposure similar to other photos in the set. However, higher ISO means also more noise in your photographs. Too much noise can make your images useless for photogrammetry.

Autofocus (AF) vs Manual focus (MF)

If you are very close to your model in bad lighting, use the autofocus (AF) point mode instead of AF area mode. In AF area mode, the camera can become confused as to where it is meant to be focusing. To be sure to get the right exposure and the focus on the model, the AF point mode is the best solution.

If you are far from your model (good or bad lighting), AF area mode is a better option as your object and background will be in focus and thus help the photo-matching process during the 3D reconstruction.

One might prefer manual focus (MF). While MF may be possible and useful in some cases (e.g., when AF mode keeps focusing on the background instead of the object), most of the time it is not an option:

- it might be very difficult to judge if you are in focus in the viewfinder

- this is time-consuming.

In any case, having everything in focus will be a problem for small objects or objects in low light. In both those instances, the depth of field will be very shallow, and the foreground and background won’t be in focus at the same time. To deal with this problem, you can increase the ISO, decrease the F-stop, increase lighting (if possible), or buy special lenses with a maximum aperture of about f/1.4 (instead of the classic f/3.5).

- Autofocus or shallow depth of field will commonly induce this problem: the background and the foreground are not in focus at the same time. This problem gets even worse in low light as the aperture is high and thus the depth of field is low.

Framing

And finally, try to get as close to the object as possible. You want to fill as much of the frame as possible with the object. The closer you are to the subject of your photos, the more pixels it will occupy in your photographs, the more information the software will have for the reconstruction, the better your final 3D model will be! Easy enough, isn’t it? If you take photographs of a detail, the object might fill the entire frame. Don’t worry about that and keep going.

6. How do you take good photographs?

And now, let’s start the photoshoot! You should think of your photoshoot like an “inward” panorama. Thus, every photograph should have something like 50-60% overlap. This overlapping is necessary for the software to match and stitch the photographs together to create the “inward” panorama. I usually start by making 3 to 4 circles around the object (see Fig. 1, below), with every circle at a different height. This technique ensures that I cover the whole object from head to toe. When doing your photoshoot, you should take photographs of the object at 360° (horizontally) and 180° (vertically).

So, going in a circle at different heights around the object helps you to keep track of your progress and ensure that you did not forget any angles (especially as you might be interrupted during the process by people moving in the frame).

In general, I take 36 photographs per circle but feel free to take more if you need them. This number corresponds to roughly 10° between each step. However, for very large objects, you might need more steps to keep the 50% overlap between each photograph. Note that if you take too few steps, you end up with photographs with 80% (or more) overlap. This will unnecessarily overload your computer during the 3D reconstruction.

Fig 1. The different dots represent the different photographs taken. The horizontal step is about 10° and the vertical step (different height) is about 30°. As the object was tall (+/- 2.50 m) the top circle over the head is missing.

Thereafter, I usually take a second round of photographs. This time, still turning around the model (+/-20° between each step), I will take 8 to 10 photographs at different heights at every step (see Fig. 2, below). The reason is the first round of photographs gives a good horizontal resolution (+/- 10° between each photograph). However, the vertical resolution of the first round is rather poor (+/- 30° between each photograph) as shown in Fig. 1. So, the second round of photographs gives a good vertical resolution (+/- 15° between each photographs) and thus compensates for the poor vertical resolution of the first round of photographs.

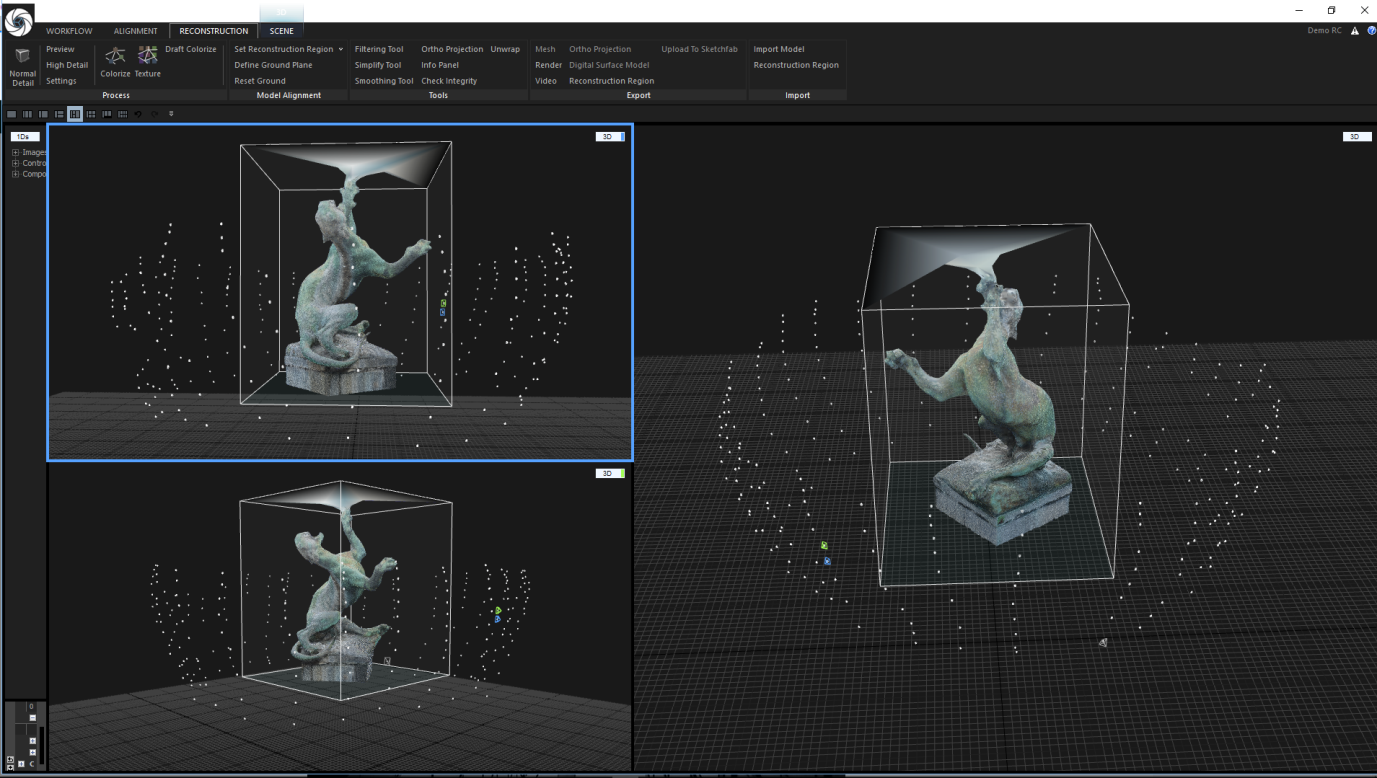

Note: The mesh artefacts that you will see below, e.g., above the top paw or above the head, are due to quick preview mode reconstructions of partial photosets.

Fig 2. The different dots represent the photographs taken. Here the horizontal step is about 20° and the vertical step (different height) is about 15°.

Last but not least, I will take photographs of specific details within the object (See Figs. 3 and 4, below). This step is very important. A successful 3D scan depends on your capacity to see the important detail and relief. In general, for sculpture, face and hands are very important, as they convey the body language that the original artist tried to express through his/her work.

This process is even more important for large objects such as buildings or landscapes. Even if the large object is in full frame, the details will represent a small part of the photographs, sometimes less than 1% of the total pixels of the photograph. In the case of a building, take additional photographs of the doors, windows, gutters, sculptures, and all other important details.

Fig 3. The different dots represent the different photographs taken around the object. In this case, additional photographs have been taken to capture the details of the torso and back paws.

Back home, you will upload all of your photos on to your computer and check them one by one. Be merciless! Delete all blurry or noisy photographs, all photographs with lens flare or bad exposure, all badly framed photographs, or photographs with people moving in the frame! It is a good habit to take more photographs than you really need, and double the shoot if you are in doubt. That way you can delete all the imperfect photographs without fear of creating a gap in your photo set.

It is better to take too many photographs than not enough! “Too much is never enough!” applies perfectly to photogrammetry. I usually end up deleting 5 to 20% of my photographs. And you do not want (or sometimes cannot) to go back and redo your photoshoot. If it is indoor, you may get lucky as the lighting condition won’t dramatically change. But outdoor photogrammetry is a whole other story—you will rarely encounter the same lighting conditions and will be forced to redo the entire photoshoot.

The final words!

That’s all folks! A good photoshoot is not only about theory but also practice. Take your camera, go wherever you want, and give it a go. I can already tell you that you will be disappointed by your first 3D scans. We all are! Just to give you a ballpark figure, I needed roughly 20 or 30 3D scans before getting the hang of it. And possibly 100 or 200 more to become a so-called “expert”. As Stephen McCranie says, “A master failed more times than the beginner has ever tried.”

I hope you have enjoyed this tutorial! Please let me know if it helped you and how I can improve it. And don’t forget to share your models below! I would love to see your results!